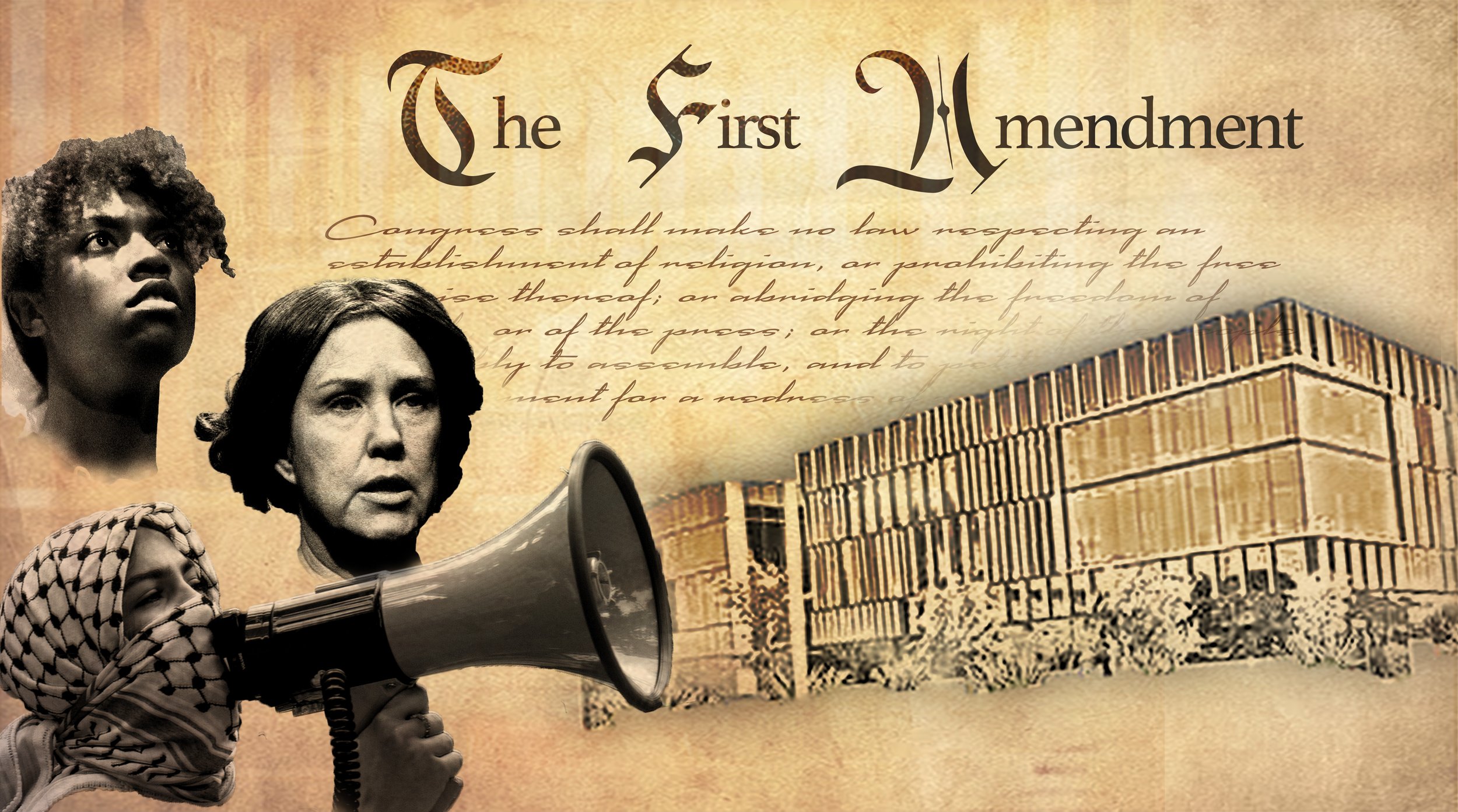

Foggy Freedoms: First Amendment Rights and Limitations in a Public College

Renée Bartlett-Webber | News Editor

SMC administration is compelled to address issues of free speech on campus in the wake of a Theatre Arts department controversy and the Israel-Hamas war

Oct. 19 was a historic day for Santa Monica College where two seemingly disparate events on campus came to a head and community members began to question their First Amendment rights. Free speech, discrimination and harassment are a few legal terms that have surfaced on campus in recent weeks. College constituent groups are now looking to the administration for support for their various causes.

The day before the premiere of the SMC theater production, “By the River Rivianna” was canceled on Oct 19. Those who opposed the play exercised their right to free speech by protesting, while the playwright and director said they were being censored. Lawyers, administrators and community members continue to discuss academic freedom within the public institution.

Meanwhile, on the same day, an Inter Council Club (ICC) meeting turned into a legal battleground as student leaders voted against installing the Student Supporting Israel (SSI) club. The administration overruled the decision citing the First Amendment the next day on Oct. 20. Stand With Us, an external organization that fights antisemitism, sent a demand letter to SMC weeks later. Students continue to struggle to understand the limitations of their own First Amendment rights.

But what do all these terms actually mean and who ultimately decides which parties or individuals are protected under the law?

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Arguments over these 45 words have been the basis of countless court cases. In Healy v. James (1972), the Supreme Court found that it was unconstitutional not to recognize a chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society. In Bethel School District v. Fraser (1986), the Court supported the school in their decision to suspend a teacher for describing a 14-year old student in a school assembly using “an elaborate, graphic, and explicit sexual metaphor.” This year, the Court found that the First Amendment prohibits Colorado from “forcing a website designer to create expressive designs for same-sex marriages, speaking messages with which the designer disagrees.”

Legal Director of the First Amendment Coalition, David Loy, told The Corsair that the First Amendment is designed to start a dialog. “That is how the First Amendment is supposed to work. There's a discussion, there's a dialog, there's a debate, and a decision is made,” he said. “[It] does not protect people against that kind of pushback, resistance, debate, critique from your peers in the community.”

But at what point does healthy debate turn into harassment, which is not protected by the First Amendment?

As defined by the California courts, civil harassment is unlawful violence or credible threat of violence and “the violence or threats seriously scare, annoy, or harass someone and there is no valid reason for it.”

“Simply being the target of criticism, of disagreement and debate, that is not necessarily harassment or bullying in general,” Loy said. “That's free speech. That's dialog. It may be harsh. It may be intense, it may be critical, it may be strong criticism, but that's what free speech is designed to protect.”

SMC legal counsel Bob Myers told the ICC club leaders at the Nov. 2 meeting, “The college does not prohibit speech simply because it’s painful, it can’t do so. There is no such thing as hate speech. There’s hate crimes, if you threaten someone because of their religion or viewpoints, that may be a hate crime. But hurtful words are not a crime and are protected by the constitution.”

In the case of the SMC production that was canceled on Oct. 19, there’s a complex dynamic that is still being disputed. Students decided to cancel the play between themselves after a vote facilitated by faculty and administration. It can be argued that it was within their First Amendment rights to come to that conclusion.

On the other hand, the playwright Burce Smith argued that the students decided to cancel because of coercion or even harassment from administration. This could be a case of censorship. Smith said there was “an unprecedented and bizarre college administration campaign of bullying and harassment.”

Director of Campus Rights Advocacy at Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) Alex Morey said, “On public campuses, the First Amendment applies in full. That includes faculty's First Amendment-protected academic freedom right to select their course content without undue government interference. Public college administrators are government actors.”

Outside of the students and faculty who were directly involved in the production, there was a community who protested before it began due to its portrayal of a romance between a Black enslaved person and his master. They were exercising their right to free speech. “I recognize that it’s a matter of academic freedom, but it's academic freedom at the expense of our Black community,” said English Department faculty member Elisa Meyer. “When the system reinforces that kind of oppression, the people being hurt have no choice but to protest.”

While the line between harassment and freedom of expression can be murky, public school systems are also covered by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act which protects against discrimination. The law states, “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

On Nov. 16, the U.S. Department of Education released a list of seven public schools that are being investigated for “antisemitism, anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and other forms of discrimination and harassment,” citing Title VI.

These same questions are poignant at SMC. On Nov. 15, SMC president Kathryn Jeffery received a demand letter from the “Stand with Us: Supporting Israel and Fighting Antisemitism” CEO Roz Rothstein among others. The letter cited Title VI of the Civil Rights Act as well as SMC policies, and requested that SMC “discipline to the fullest extent” the student leaders who “engaged in discrimination against Jews or Israelis.” Additionally, the letter requested that the school publish a statement identifying the measures they have taken to combat antisemitism and that all future allegations “will be investigated and met with a zero tolerance policy.”

This letter was in response to the events at the ICC meeting on Oct. 19, when 10 club leaders voted against installing the SSI club because they said the club pushed a political ideology onto students. After a social media backlash from the national SSI movement, the administration reinstated the club within 24 hours of the vote.

Associate Dean of Student Life, Thomas Bui, told the Corsair, “The reason why we reinstated the Students Supporting Israel very quickly is because by law, we had no legal basis to not have installed that student club, regardless of people’s opinions or thoughts about any student organization.” He explained that all student clubs are protected by the First Amendment.

In the Nov. 2 ICC meeting, Myers told the student government leaders, “You act in the name of the Santa Monica Community College District which is required to comply with the law. It is the role of administrators at the college to ensure lawful decisions.”

Since the meeting, many students have expressed that the allegations of antisemitism are false and a form of defamation. Middle Eastern Club president, who requested not to be identified by name due to fear of doxxing, said “SMC and SSI are changing the narrative of us speaking up for our members or justice as being antisemitic, which has been a pattern for a long time.” She added that she is trying to hold them accountable for “false allegations and slander.”

Rabbi Eli Levitansky, leader of the Chabad Jewish club, said he thinks the administration should show stronger support to Jewish students who experienced discrimination after that meeting. “I’m not a legal expert, I am an advocate for free speech and I know that includes hate speech, I understand that. But at the same time, I think that the administration can actively be much stronger in their condemnation of this type of rhetoric.”

As Loy stated, the First Amendment is intended to spark discussion and debate between community members without the intervention of government actors and ultimately they should come to a decision together. But with topics that polarize the community, the path forward can become murky as shown with many legal cases that are taken all the way to the Supreme Court.

Students, faculty and community members are now looking to the SMC administration to voice support for the various causes on campus in hopes for justice to the communities. Administrators are caught in legal crosshairs as they are forced to navigate the gray areas of free speech, censorship and discrimination.

On Oct. 28, SMC President Kathryn Jeffery sent an email to all faculty acknowledging the challenges of the last few weeks citing both the “ongoing conflict in another part of the world” and “difficult conversations” around the play. She said “to facilitate a path forward,” there will be college-wide forums that will be scheduled “over the next few weeks.” There has been no update as to when these meetings will occur, but Jeffery sent a statement to the Corsair saying, “I have met with sub-groups representing multiple college constituency groups.” She said the hope is to create a space for necessary, respectful dialog.

Los Angeles residents form roving patrols to identify Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and operations.